Do good writers use fewer adverbs than poor writers? Is it possible to improve ones writing by looking at the relative distribution of different parts of speech (POS)? I was curious about this and wanted to investigate. The first step towards determining this is to find out what a “normal” POS distribution is. To do that, we’ll explore parts of speech usage in Great Expectations by Charles Dickens.

from urllib import request

import nltk

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

We’ll use the technique described in the post on Getting text from Project Gutenberg to gather the text of Great Expectations.

# Now let's grab some text from Great Expectations

url = 'http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1400/1400-0.txt'

response = request.urlopen(url)

raw = response.read().decode('utf8')

print(raw[:200])

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Great Expectations, by Charles Dickens

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it

The raw text begins and ends with a preamble from Project Gutenberg that we don’t want to include in our analysis, so we’ll remove it. It also ends with some extra text which we won’t include either.

text = raw[886:-19150] # Jumping to where it actually starts

# Print the beginning to test

print(text[:205])

My father’s family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my

infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit

than Pip. So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.

That looks good. Now we’ll use the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) to split the text into tokens for further analysis.

tokens = nltk.word_tokenize(text)

print(tokens[:20])

['My', 'father', '’', 's', 'family', 'name', 'being', 'Pirrip', ',', 'and', 'my', 'Christian', 'name', 'Philip', ',', 'my', 'infant', 'tongue', 'could', 'make']

Now let’s tag all the tokens with their parts of speech. NLTK has a part of speech tagger built in.

# Now we have to tag all the words

tagged = nltk.pos_tag(tokens)

print(tagged[:20])

[('My', 'PRP$'), ('father', 'NN'), ('’', 'NN'), ('s', 'VBP'), ('family', 'NN'), ('name', 'NN'), ('being', 'VBG'), ('Pirrip', 'NNP'), (',', ','), ('and', 'CC'), ('my', 'PRP$'), ('Christian', 'JJ'), ('name', 'NN'), ('Philip', 'NNP'), (',', ','), ('my', 'PRP$'), ('infant', 'JJ'), ('tongue', 'NN'), ('could', 'MD'), ('make', 'VB')]

To see what the various tags mean, you can run nltk.help.upenn_tagset(). Now that each word is tagged we can combine all the nouns into one list, verbs into another, etc.

# Note that IN can be either a preposition or a conjunction, for now we're going to list it with the prepositions

common_noun_pos = ['NN', 'NNS']

common_nouns = []

verb_pos = ['VB', 'VBD', 'VBG', 'VBN', 'VBP', 'VBZ']

verbs=[]

adjective_pos = ['JJ', 'JJR', 'JJS']

adjectives = []

pronoun_pos = ['PRP', 'PRP$', 'WP', 'WP$']

pronouns = []

adverb_pos = ['RB', 'RBR', 'RBS', 'WRB']

adverbs = []

proper_noun_pos = ['NNP', 'NNPS']

proper_nouns = []

conjunction_pos = ['CC']

conjunctions = []

preposition_pos = ['IN', 'TO']

prepositions = []

interjection_pos = ['UH']

interjections = []

modal_pos = ['MD'] # But these are also verbs, so let's make sure they show up as such

modals = []

tagged_other_pos = ['CD', 'DT', 'EX', 'FW', 'LS', 'PDT', 'POS', 'RP', 'SYM', 'WDT']

tagged_others = []

other = []

for idx, token in enumerate(tagged):

if token[1] in common_noun_pos:

common_nouns.append(token)

elif token[1] in verb_pos:

verbs.append(token)

elif token[1] in adjective_pos:

adjectives.append(token)

elif token[1] in pronoun_pos:

pronouns.append(token)

elif token[1] in adverb_pos:

adverbs.append(token)

elif token[1] in proper_noun_pos:

proper_nouns.append(token)

elif token[1] in conjunction_pos:

conjunctions.append(token)

elif token[1] in preposition_pos:

prepositions.append(token)

elif token[1] in interjection_pos:

interjections.append(token)

elif token[1] in modal_pos:

modals.append(token)

elif token[1] in tagged_other_pos:

tagged_others.append(token)

else:

other.append(token) # all the punctuation goes here

parts_of_speech = [common_nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, adverbs, proper_nouns, conjunctions, prepositions, interjections, modals]

# Added modals to verbs

# Create nouns that is both proper nouns and common nouns

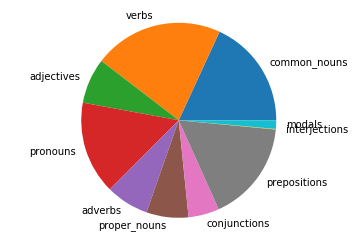

Now we’ve got a lists of the different parts of speech, let’s visualize it. We’ll make a function that makes a pie chart with the data.

# From the Part of Speech notebook:

# OK, but we haven't made a way to visual the results yet. Let's do that now with a pie chart

def pos_plotter(parts_of_speech):

'''This function inputs a specific list of lists that is shown in the Part of Speech notebook'''

all_labels = ['common_nouns', 'verbs', 'adjectives', 'pronouns', 'adverbs', 'proper_nouns', 'conjunctions', 'prepositions', 'interjections', 'modals']

pos_dict = dict(zip(all_labels, parts_of_speech))

labels=[]

data=[]

for pos, lst in pos_dict.items():

if lst:

data.append(len(lst))

labels.append(pos)

fig1, ax1 = plt.subplots()

ax1.pie(data, labels=labels)

ax1.axis('equal') # Equal aspect ratio ensures that pie is drawn as a circle.

plt.show()

pos_plotter(parts_of_speech)

Now that we’ve worked through one example, we’ll build a more formalized method of exploring other texts in Part 2. We’ll also explore ways to compare across texts.