In geographical information systems (GIS) it’s important to know how to manipulate geometric data. The best tool for this in Python is Shapely, which provides an extensive set of operations that allow for the sophisticated analysis of spatial data. In this post, I give an introduction to working with Shapely. PostGIS data is usually in the form of WKB or WKT, so we’ll talk about how to work with those data types.

Table of Contents

- Shapely Objects

- Shapely Operations

- Visualizing Shapely Polygons

- Shapely and Well-Known Text (WKT)

- Shapely and Well-Known Binary (WKB)

- Pandas Representations

- GeoJSON to Shapely

- Other Notes

import binascii

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

from rtree import index

from shapely import wkt

from shapely.geometry import LineString, MultiPolygon, Point, Polygon, shape

from shapely.ops import unary_union

from shapely.wkb import dumps as wkb_dumps

from shapely.wkb import loads as wkb_loads

from shapely.wkt import dumps as wkt_dumps

from shapely.wkt import loads as wkt_loads

Shapely Objects

Shapely operates on objects like points, lines, and polygons, which are the fundamental elements of planar geometry. In GIS, a ‘geom’ refers to any geometric shape, such as points, lines, and polygons. A shapely polygon is a geom.

Points

Points are the most basic form of a geometric object. In Shapely, a point is represented by its x and y coordinates.

point = Point(0, 0)

point

Lines

Lines or LineStrings in Shapely are formed by connecting a sequence of points.

line = LineString([(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2)])

line

Polygons

A polygon is a two-dimensional shape formed by a closed, non-intersecting loop of points. A simple polygon in Shapely is created by passing a sequence of (x, y) coordinate tuples that form the exterior boundary. The first and last point in the sequence must be the same.

polygon = Polygon([(0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (0, 1), (0, 0)])

polygon

Polygons with Holes

Polygons can have holes, defined by one or more interior rings. To create a polygon with one or more holes, you pass a list of exterior coordinates and a list of one or more lists of interior coordinates.

exterior = [(0, 0), (5, 0), (5, 5), (0, 5), (0, 0)]

hole = [(1, 1), (4, 1), (4, 4), (1, 4), (1, 1)]

polygon_with_hole = Polygon(exterior, [hole])

polygon_with_hole

Shapely polygons have various useful attributes and methods. For example, you can get the area, the boundary, the centroid, the length of the exterior, and check if the polygon is valid.

print("Area:", polygon_with_hole.area)

print("Boundary:", polygon_with_hole.boundary)

print("Centroid:", polygon_with_hole.centroid)

print("Length of Exterior:", polygon_with_hole.length)

print("Is valid:", polygon_with_hole.is_valid)

Area: 16.0

Boundary: MULTILINESTRING ((0 0, 5 0, 5 5, 0 5, 0 0), (1 1, 4 1, 4 4, 1 4, 1 1))

Centroid: POINT (2.5 2.5)

Length of Exterior: 32.0

Is valid: True

Multipolygons

A Multipolygon is a collection of polygons that are treated as a single entity. They are useful for representing disconnected regions or islands. Shapely can handle operations on Multipolygons similar to simple polygons.

# Define two simple polygons

polygon1 = Polygon([(0, 0), (2, 0), (2, 2), (0, 2)])

polygon2 = Polygon([(3, 3), (5, 3), (5, 5), (3, 5)])

# Create a multipolygon from the two polygons

multipolygon = MultiPolygon([polygon1, polygon2])

multipolygon

Shapely Operations

After mastering the creation of polygons in Shapely, the next step is to explore the variety of operations that can be performed on these shapes. This section dives into some of the most common and powerful spatial operations available in Shapely.

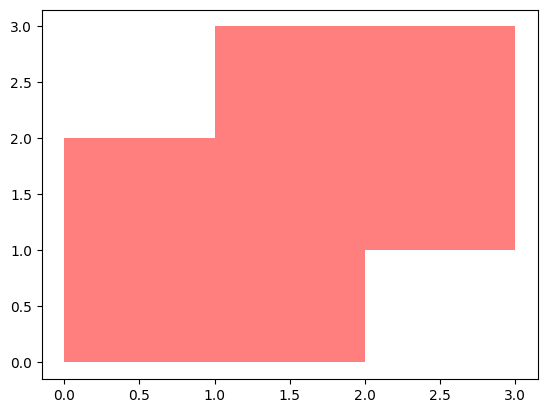

Union

The union combines two or more polygons into a single shape, merging their area.

poly1 = Polygon([(0, 0), (2, 0), (2, 2), (0, 2)])

poly2 = Polygon([(1, 1), (3, 1), (3, 3), (1, 3)])

union_poly = unary_union([poly1, poly2])

union_poly

Intersection

The intersection finds the common area shared between two or more polygons.

intersect_poly = poly1.intersection(poly2)

intersect_poly

Difference

The difference subtracts the area of one polygon from another.

diff_poly = poly1.difference(poly2)

diff_poly

Symmetric Difference

The symmetric difference returns the area which is in either of the polygons but not in their intersection.

sym_diff_poly = poly1.symmetric_difference(poly2)

sym_diff_poly

Buffering

Buffering creates a polygon around a shape at a specified distance. This is particularly useful in spatial analysis for creating zones or areas of influence.

buffered_poly = poly1.buffer(0.5)

buffered_poly

Convex Hull

The convex hull calculates the convex hull of a polygon, a smallest convex shape that encloses all points of the polygon.

hull_poly = poly1.convex_hull

hull_poly

Bounding Box

The bounding box computes the bounding box for a polygon, which is the smallest rectangle that completely encloses the polygon.

bbox = poly1.bounds

bbox

(0.0, 0.0, 2.0, 2.0)

Visualizing Shapely Polygons

You can visualize Shapely polygons in Jupyter Notebooks just by running them like I have here. But if you’re not in a Jupyter Notebook, you may want to use Matplotlib or GeoPandas. Here’s an example using Matplotlib:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

x,y = union_poly.exterior.xy

ax.fill(x, y, alpha=0.5, fc='r', ec='none')

plt.show()

Shapely and Well-Known Text (WKT)

Well-Known Text (WKT) is a text markup language for representing vector geometry objects on a map. It is widely used in GIS and spatial databases for easy exchange and storage of geometric data. WKT often serves as a bridge for geometric data between different systems or software. In this section, I’ll show how to convert Shapely polygons to and from WKT format.

Shapely polygons can be converted to WKT using the wkt property. This feature is particularly useful when you need to store or share geometric data in a standardized format.

Shapely Polygon to WKT

point = Point(0, 0)

wkt_data = point.wkt

wkt_data

'POINT (0 0)'

polygon = Polygon([(0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (0, 1)])

wkt_data = polygon.wkt

wkt_data

'POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))'

WKT to Shapely Polygon

Shapely can convert WKT strings back into Shapely geometric objects. This is useful when working with spatial data extracted from databases or external files.

wkt_data = "POINT (0 0)"

shapely_geom = wkt_loads(wkt_data)

shapely_geom

Shapely and Well-Known Binary (WKB)

Well-Known Binary (WKB) is another standard format used in GIS for storing and transferring geometric data. WKB is a binary encoding of geometric data, designed to be compact and efficient for storage and transport. Like WKT, WKB represents geometries such as points, lines, and polygons, but in a compact, binary form that is not human-readable. WKB is more space-efficient than WKT, making it better suited for storing large amounts of spatial data. It is widely supported across various GIS systems and spatial databases. This section explores how WKB is used in conjunction with Shapely polygons.

Shapely supports exporting polygons to WKB format, which can be useful for storing or transmitting geometric data.

Shapely Polygon to WKB

WKB can be represented in either binary or hexadecimal representation. You can use dumps to put it in either.

polygon = Polygon([(0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (0, 1)])

# Convert the polygon to WKB binary representation

wkb_binary = wkb_dumps(polygon, hex=False) # this is the default

# Convert the polygon to WKB hexadecimal representation

wkb_hex = wkb_dumps(polygon, hex=True)

print("WKB Binary:", wkb_binary)

print("WKB Hexadecimal:", wkb_hex)

WKB Binary: b'\x01\x03\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\x05\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xf0?\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xf0?\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xf0?\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\xf0?\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'

WKB Hexadecimal: 0103000000010000000500000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000F03F0000000000000000000000000000F03F000000000000F03F0000000000000000000000000000F03F00000000000000000000000000000000

WKB to Shapely Polygon

You can convert either back to a Shapely Polygon.

shapely_polygon = wkb_loads(wkb_binary)

shapely_polygon

Note that before Shapely 2.0, you had to convert a hexadecimal representation into a binary representation before converting it into a Shapely Polygon.

# Convert the polygon to WKB hexadecimal representation

wkb_hex = wkb_dumps(shapely_polygon, hex=True)

# Convert the hexadecimal string to binary

wkb_binary = binascii.unhexlify(wkb_hex)

# Convert the binary WKB back into a Shapely polygon

converted_polygon = wkb_loads(wkb_binary)

print("Original Polygon:", shapely_polygon)

print("WKB Hexadecimal:", wkb_hex)

print("Converted Polygon:", converted_polygon)

Original Polygon: POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

WKB Hexadecimal: 0103000000010000000500000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000F03F0000000000000000000000000000F03F000000000000F03F0000000000000000000000000000F03F00000000000000000000000000000000

Converted Polygon: POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

shapely_polygon = wkb_loads(wkb_hex)

shapely_polygon

Practical Use-Cases of WKB

WKB is ideal for storing spatial data in databases or transmitting it over networks due to its compact size. It is particularly useful in environments where bandwidth or storage efficiency is a concern. Many spatial databases use WKB as their native format for storing geometric data, which allows for efficient data exchange between Shapely and these databases.

Pandas Representations

It’s worth pointing out something about how Shapely objects are represented in pandas. They look like strings in the output, but they are not. This can lead to confusion. Let’s look at an example where we have a pandas Series of well-known text, which are stored as strings.

polygon = Polygon([(0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (0, 1)])

wkt_data = polygon.wkt

wkt_series = pd.Series([wkt_data]*5)

wkt_series

0 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

1 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

2 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

3 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

4 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

dtype: object

print(type(wkt_series.iloc[0]))

wkt_series.iloc[0]

<class 'str'>

'POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))'

Because it’s a string we can’t, for example, create an r-tree out of them.

try:

idx = index.Index()

for pos, geom in enumerate(wkt_series):

idx.insert(pos, geom.bounds)

except AttributeError as e:

print(f"Ran into error: {e}")

Ran into error: 'str' object has no attribute 'bounds'

Now, let’s convert them to Shapely objects.

def convert_to_shapely_geom(wkt_geom):

try:

return wkt.loads(wkt_geom)

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error converting WKT to geometry: {e}")

return None

shapely_series = wkt_series.apply(convert_to_shapely_geom)

shapely_series

0 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

1 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

2 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

3 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

4 POLYGON ((0 0, 1 0, 1 1, 0 1, 0 0))

dtype: object

When we look at it in pandas, it looks the same. This can be confusing because it’s a Shapely Polygon now. You can see the difference when you run a single one in a cell.

print(type(shapely_series.iloc[0]))

shapely_series.iloc[0]

<class 'shapely.geometry.polygon.Polygon'>

Now, we can create an r-tree with it.

idx = index.Index()

for pos, geom in enumerate(shapely_series):

idx.insert(pos, geom.bounds)

GeoJSON to Shapely

We can also convert GeoJSON data to Shapely.

geom_data = {

"type": "Polygon",

"coordinates": [

[(0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (0, 1), (0, 0)]

]

}

shapely_polygon = shape(geom_data)

shapely_polygon

Other Notes

Performance Tips for Large Datasets

Working with large spatial datasets can be challenging. Here are some tips to improve performance:

Use Geometric Simplification

Simplifying geometry reduces the number of vertices and can significantly speed up operations without losing much detail. Shapely provides the .simplify() method for this purpose.

Spatial Indexing

For operations involving multiple geometries, such as intersection tests, use spatial indexing to reduce computation. Libraries like RTree or PyGEOS can be integrated with Shapely for efficient spatial indexing.

Coordinate Systems and Projections

Shapely does not handle coordinate system transformations. It’s essential to ensure that all your geometries are in the same coordinate system before performing operations.