Selecting and evaluating a dataset to use for training a machine learning model is an essential step in the process. It’s far more important than having the latest architecture or doing the most detailed hyperparameter tuning. It’s probably the most important aspect of the process other than asking the right questions in the first place.

\[Question > Dataset > Algorithm\]But how do we evaluate a dataset? What questions should we ask? In this post, I’m going to talk about how I evaluate imagery datasets and some key questions to ask when doing so. Some of the questions will apply to all machine learning datasets, but many of them are specific to imagery. There will also be domain-specific questions depending on what domain you’re working in.

Table of Contents

- Overall

- Datasets Statistics

- Metadata

- Label Noise

- Is the Task Possible?

- Thinking Through a Solution

- Data Labeling

- Conclusion

Overall

First I like to just look at lots of images to get an idea of it. What’s my overall impression of the imagery? What kind of variation is there (color, contrast, size, resolution, etc.)? Sure, I’ll learn a lot of this from analyzing the metadata, but before I get too many ideas in my head from metadata or reading what the authors say about the data, I like to get a good idea for myself. I want to know its pluses, minuses, and any biases in the data.

Dataset Distribution

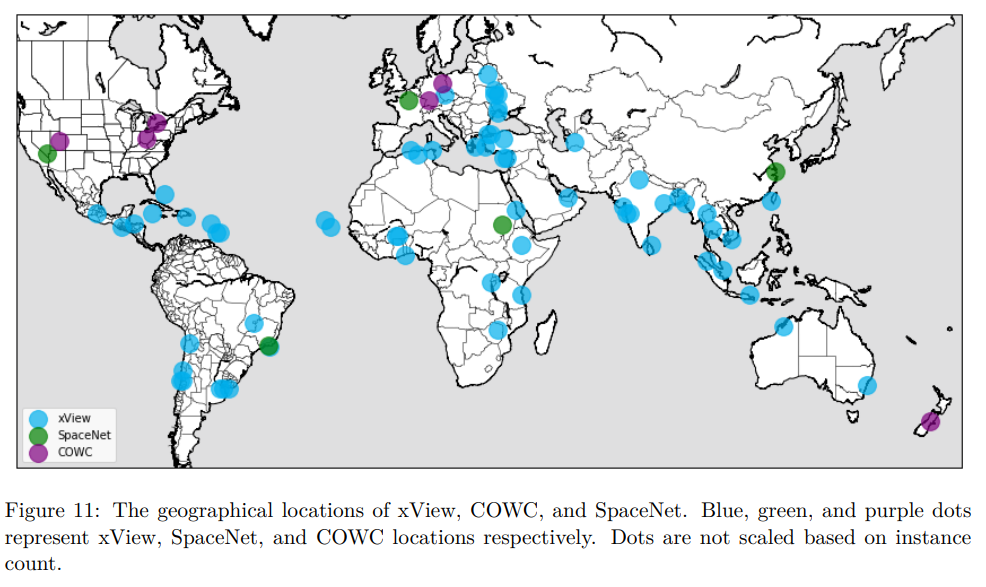

Some of the questions will be based on the task. For example, if you’re going to build a world-wide detector of, say, airplanes, do you have all terrains represented? What’s the geographic distribution? I like to first look at the imagery and start to answer this. Then I’ll use the metadata to confirm.

Some datasets, such as xView, actually show the distribution of the data. In geospatial data, you’re often asking where all areas are well-represented. But for medical data, you’re probably more interested in demographics - ages, races, general health, etc.

Datasets Statistics

This is where the metadata comes in. I like to do a good analysis of the metadata. I like to understand what are the general dataset parameters? How many images are there, how many objects per image on average, etc. What’s the distribution of the different classes? Beware of the long-tailed distribution. If you’re doing many classes, you need to be sure there are enough examples for the less-common cases. Sure, there are lots of examples of the most common objects, but what about the difficult ones? For the nth most common class, how many labels do they have?

Metadata

Is there metadata associated with the dataset? If so, it’s good to look at the raw metadata. Is the formatting consistent? Does it seem reasonable? If there are errors, how easily correctable are they?

Label Noise

Some datasets, primarily toy datasets, are very clean. If you look at the famous iris dataset, you will find that it has no missing data, no inaccurate information, and is perfectly balanced between the cases. This is the kind of thing you would only see in a toy dataset. The vast majority of real-world datasets are quite noisy.

In general, it helps to be as quantitative as possible. If you can look at 100 images and write down exactly how many have this or that problem, that’s ideal.

It’s not just the labels that can be noisy - are there blank images? Duplicates?

It’s good to visualize the images with the labels overlaid. Some datasets, like DOTA, provide tools that make this easy. Some datasets don’t.

Be critical when judging the labeled imagery. This isn’t the time for saying, “Oh, I know what you meant.” A bounding box that is off by a bit means you are explicitly telling the model that that object is not what you are looking for. Computers are dumb. Think dumb.

I don’t mean to imply that models cannot deal with label noise - they certainly can - but you want to know what you’re getting into.

Are there “bad” images? In this case of geospatial analytics, these might be cloudy images. If so, will you need something like a cloud detector to filter them out?

Is the Task Possible?

Can a Human Do It?

Can you answer the proposed question with the dataset? By “you”, I mean “you” as a human. Sometimes, especially in geospatial analytics, your imagery is barely good enough to see the objects. If you can’t identify them your algorithm mostly likely won’t be able to either. If it’s a multi-class problem, can YOU tell the classes apart?

Is there sufficient information in the image to find the objects? Would it be easy for a human? After you’ve looked through a lot of images, are there patterns that a human could use? (And are there examples of data leakage). What biases are there in the data? Are there systematic biases? Will you need to correct for them? Do all the images of one class look different than images with another class (e.g. all the bird pictures have a blue background, and all the snake pictures have green)? This isn’t necessarily a bad thing - you just have to make sure you understand if this difference will be valid in production as well - but it’s something you’ll need to know. Try to see both the forest and the trees.

Can a Computer Do It?

Then think about how a computer would classify the images. How would a computer distinguish between the classes? This is not always easy to know and sometimes won’t know - that’s OK.

Thinking Through a Solution

Think about the difficulty of the overall task, given the objects. What objects make sense to combine into a multi-class classifier. What would best be done as a single class classifier?

Could pre-processing the imagery help with the task?

How could you transform it to help?

What architecture might you use, and how would it solve this problem. Will you need to pick out small details? Is the minimal kernel size small enough to pick out the necessary features?

For the objects, are the local features of the object sufficient to classify them, or do you need some surrounding context? Sometimes you’ll be distinguishing between different rectangles (trucks vs. AC units on buildings), and you’ll need context. This makes classification more challenging. Are there other things that look like the objects you’re trying to detect (so-call non-target distractors)? If so, you might want to think about labeling them directly as well. If your car detector has problems distinguishing between cars and bushes, one possible solution is to use hard-negative mining on the bushes. Labeling them makes this possible.

Data Labeling

If it’s prelabeled data, it’s always good to know about the labeling process as well. You’d like to know how the labels were generated - was it a single person or multiple people per image? Were their decisions combined like votes? Do you have access to the raw “votes”? You’re likely going to find lots of noise in any real-world dataset. What other information did the labelers provide? Image quality scores? Confidence?

Conclusion

If you take one thing away from this post, I hope it’s that the dataset is more important than the algorithm, and the questions being asked of the data are the most important of all. It’s worth repeating:

\[Question > Dataset > Algorithm\]There are a bunch of specific questions in this post, but by going through a bunch of images you’ll also get answers to all the questions that are too silly to ask but just as important - are there lots of duplicates? Are some images impossible to read or corrupted? Etc. This is only a guide to help you think through the process, but take note of anything you think is relevant.