Distributions are super important. In this post, I’ll talk about some common distributions, how to plot them, and what they can be used for.

Table of Contents

Distributions can be categorized as discrete or continuous based on whether the variable is discrete or continuous.

import math

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

from scipy.stats import binom, norm, pareto, poisson, lognorm

# set seed

np.random.seed(0)

Continuous Distributions

Continuous Uniform Distribution

The most basic distribution is the uniform distribution. In this case every value between the limits is equally likely to be selected. These can be continuous or discrete. Continuous uniform distributions are also called rectangular distributions.

Plot

def plot_hist(

data,

num_bins=20,

*,

ax=None,

color='g',

xlabel='Variable',

ylabel='Count',

title_prefix='Continuous Uniform Distribution',

**hist_kw,

):

ax = ax or plt.gca()

ax.hist(data, bins=num_bins, color=color, alpha=0.9, **hist_kw)

ax.set_xlabel(xlabel)

ax.set_ylabel(ylabel)

ax.set_title(f'{title_prefix} with {num_bins} bins')

return ax

num_samples = 10000

x = np.random.uniform(0, 1, num_samples)

num_bins = 20

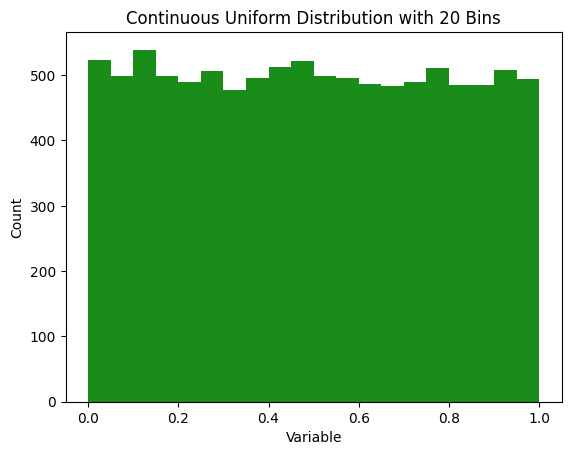

plot_hist(x, num_bins=20);

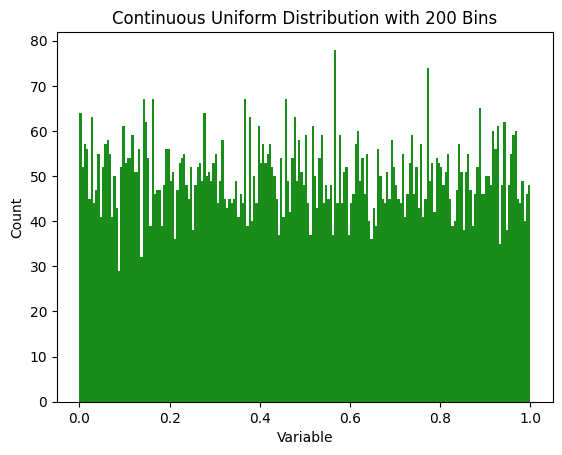

Note that the number of bins used to plot it can make it look more or less spiky. Here’s the same data plotted with 200 bins.

num_bins = 200

count, bins, ignored = plt.hist(x, bins=num_bins, color='g', alpha=0.9)

plot_hist(x, num_bins=200);

Uses

Whether things are truly continuously distributed or not can be a bit of a question of definition. If time and space are quantized, then nothing in the physical world is truly a continuous uniform distribution. But these things are close enough. Some uniform distributions are:

- Random number generators (in the ideal case)

- If buses run on an exact hourly schedule and you show up at a random time, your waiting time is uniformly distributed between 0 and 60 minutes.

- Timing of asteroid impacts (roughly - it would only be continuous given a steady state of the universe, so doesn’t work for very long time scales)

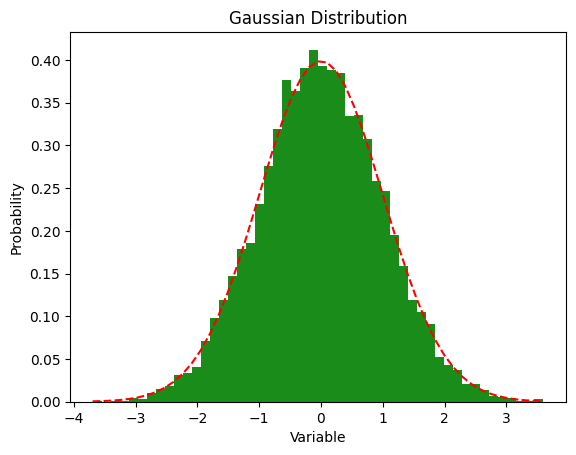

Gaussian (or Normal) Distribution

Gaussian distributions are all around us. These are the famous bell curves. I’ve found that physicists are more likely to say “Gaussian” and mathematicians are more likely to say “normal”. It seems that “normal” is more popular, although old habits die hard, so I still say “Gaussian”.

Equation

\[f(x) = \frac{e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}}{\sqrt{2\pi} }\]Or, with more parameters:

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi} } e^{-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2}\]Many distributions look roughly Gaussian but are not truly Gaussian. A paper on “The unicorn, the normal curve, and other improbable creatures” looked at 440 real datasets and found that none of them were perfectly normally distributed.

Plot

fig = plt.figure()

mean = 0

standard_deviation = 1

x = np.random.normal(loc=mean, scale=standard_deviation, size=num_samples)

num_bins = 50

n, bins, patches = plt.hist(x, num_bins, density=True, color='g', alpha=0.9)

# add a line

y = norm.pdf(bins, loc=mean, scale=standard_deviation)

plt.plot(bins, y, 'r--')

plt.xlabel('Variable')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.title("Gaussian Distribution")

plt.show()

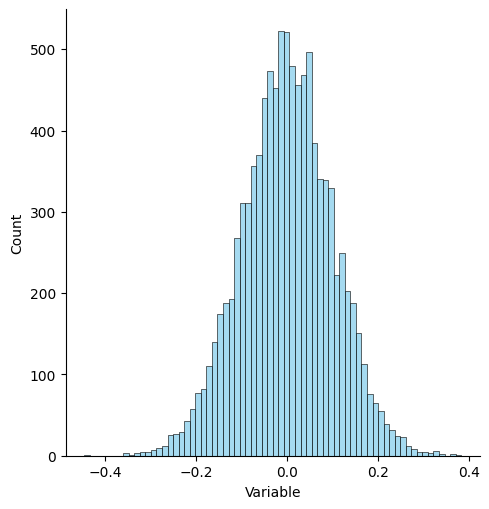

You can also do this with seaborn and displot.

mu, sigma = 0, 0.1 # mean and standard deviation

s = np.random.normal(mu, sigma, num_samples)

ax = sns.displot(s, color='skyblue')

ax.set(xlabel='Variable', ylabel='Count');

Uses

- Height is a famous example of a Gaussian distribution

- Test scores on standardized tests are roughly Gaussian

- Blood pressure of healthy populations

- Birth weight

Log-Normal Distribution

The log-normal distribution models a random variable whose logarithm is normally distributed. It is only defined for positive values and often arises when many independent factors multiply together. Testosterone levels in human populations are typically right-skewed, so they’re commonly modeled with a log-normal distribution.

Equation

\[f(x; \mu, \sigma) = \frac{1}{x \sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left( -\frac{(\ln x - \mu)^2}{2\sigma^2} \right),\quad x>0\]Plot

from scipy.stats import lognorm

fig = plt.figure()

mu = 0

sigma = 0.5

x = np.random.lognormal(mean=mu, sigma=sigma, size=num_samples)

num_bins = 50

counts, bins, ignored = plt.hist(x, num_bins, density=True, color='g', alpha=0.9)

# add a line

y = lognorm.pdf(bins, s=sigma, scale=np.exp(mu))

plt.plot(bins, y, 'r--')

plt.xlabel('Variable')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.title('Log-Normal Distribution')

plt.show()

Uses

- Modeling incomes and stock prices

- Sizes of particles or organisms

- Time to complete tasks when influenced by many small multiplicative factors

- Testosterone levels in human populations

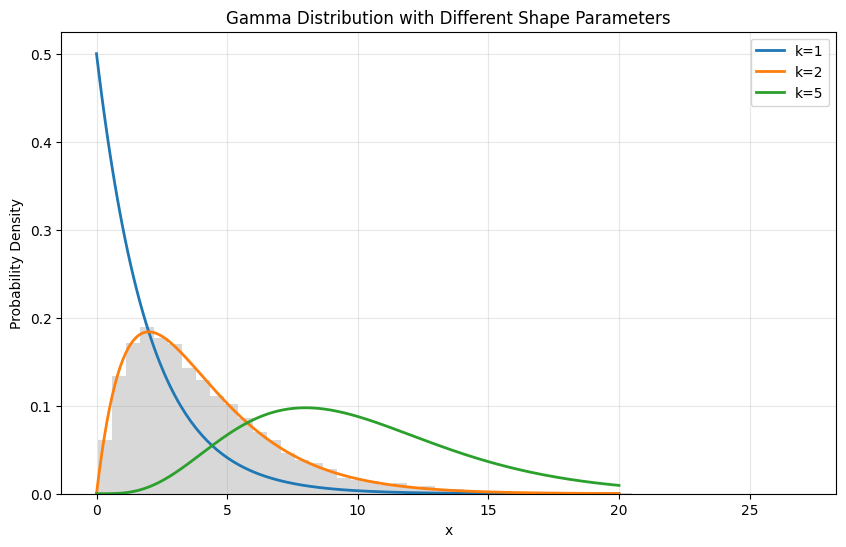

Gamma Distribution

The Gamma distribution is a continuous probability distribution that generalizes the Erlang distribution to non-integer shape parameters. It’s a versatile distribution that can model right-skewed data and waiting times, making it particularly useful in various fields from finance to engineering.

When the shape parameter is an integer, the Gamma distribution reduces to an Erlang distribution (which we’ll see next), and when the shape parameter equals 1, it becomes an exponential distribution. This flexibility makes it a fundamental building block in probability theory and statistical modeling.

Equation

The probability density function of the Gamma distribution is:

\[f(x; k, \theta) = \frac{x^{k-1}e^{-x/\theta}}{\theta^k\Gamma(k)}\]where:

- x > 0 is the random variable

- k > 0 is the shape parameter

- θ > 0 is the scale parameter

- Γ(k) is the Gamma function

The Gamma function Γ(k) is defined as:

\[\Gamma(k) = \int_0^\infty t^{k-1}e^{-t}dt\]Plot

from scipy.stats import gamma

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Set parameters

shape_params = [1, 2, 5] # k parameters

scale = 2.0 # θ parameter

num_samples = 10000

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

# Plot PDF for different shape parameters

x = np.linspace(0, 20, 200)

for k in shape_params:

plt.plot(x, gamma.pdf(x, a=k, scale=scale),

label=f'k={k}', lw=2)

# Generate and plot histogram for one case

samples = gamma.rvs(a=2, scale=scale, size=num_samples)

plt.hist(samples, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.3, color='gray')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('Probability Density')

plt.title('Gamma Distribution with Different Shape Parameters')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

Uses

The Gamma distribution finds applications in many fields:

- Finance: Modeling insurance claims and asset returns

- Weather: Analyzing rainfall amounts and other precipitation data

- Engineering: Lifetime modeling of components and systems

- Biology: Modeling waiting times between cell divisions

- Physics: Describing particle interactions and decay processes

- Healthcare: Patient recovery times and treatment durations

- Queueing theory: Service times in complex systems

It’s particularly useful when modeling:

- Continuous, positive-valued random variables

- Right-skewed distributions

- Processes involving waiting times or durations

- Situations where events accumulate over time

For example, in reliability engineering, the Gamma distribution can model the time until failure for systems where damage accumulates gradually over time, like wear and tear on mechanical components.

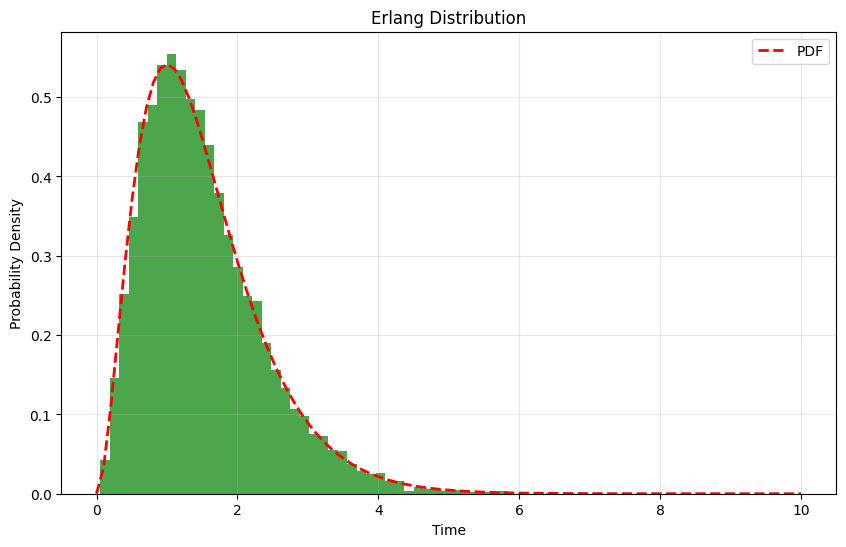

Erlang Distribution

The Erlang distribution is a continuous probability distribution that describes the waiting time until k independent events occur in a Poisson process. It’s named after Agner Krarup Erlang, who developed it to examine the number of telephone calls that could be made simultaneously to the operators of the early telephone exchanges.

The Erlang distribution is a special case of the Gamma distribution where the shape parameter k is an integer. This makes it particularly useful for modeling scenarios where you’re waiting for a specific number of events to occur sequentially.

Equation

The probability density function of the Erlang distribution is:

\[f(x; k, \lambda) = \frac{\lambda^k x^{k-1} e^{-\lambda x}}{(k-1)!}\]where:

- x ≥ 0 is the random variable

- k is the shape parameter (a positive integer)

- λ > 0 is the rate parameter

- (k-1)! is the factorial of (k-1)

Plot

from scipy.stats import erlang

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Set parameters

shape = 3 # k parameter

rate = 2.0 # λ → mean = 1 / λ = 0.5

scale = 1 / rate # θ (what SciPy expects)

num_samples = 10000

# Generate random samples

x = erlang.rvs(shape, scale=scale, size=num_samples)

# Create the plot

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.hist(x, bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.7, color='g')

# Add the PDF

x_pdf = np.linspace(0, 10, 100)

plt.plot(x_pdf, erlang.pdf(x_pdf, shape, scale=scale),

'r--', lw=2, label='PDF')

plt.xlabel('Time')

plt.ylabel('Probability Density')

plt.title('Erlang Distribution')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

Uses

The Erlang distribution is particularly useful in queuing theory and reliability engineering. Some common applications include:

- Call center modeling: Time until k calls are completed

- Manufacturing: Time until k items are produced

- Quality control: Time until k defects are detected

- Network traffic: Time until k packets arrive

- Maintenance scheduling: Time until k components need replacement

- Service systems: Time to complete k sequential tasks

The distribution is especially valuable when modeling systems where events must occur in sequence, like multi-stage manufacturing processes or sequential service operations. For instance, in a three-stage manufacturing process, the total production time would follow an Erlang distribution with k=3, assuming each stage takes an exponentially distributed amount of time.

Discrete Distributions

Lots of distributions aren’t continuous, they model discrete outcomes. For example, you can’t flip 7.5 heads after 15 tries.

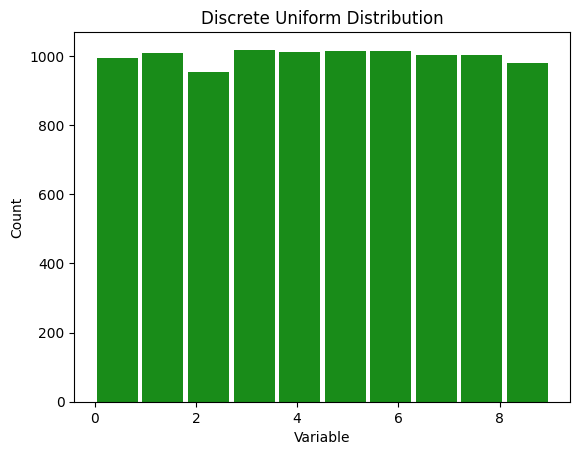

Discrete Uniform Distribution

Lots of things are discrete uniform distribution.

Plot

x = np.random.randint(0, 10, num_samples)

count, bins, ignored = plt.hist(x, color='g', alpha=0.9, rwidth=0.9)

num_bins = len(bins) - 1

plt.xlabel('Variable')

plt.ylabel('Count')

plt.title(f"Discrete Uniform Distribution")

plt.show()

Uses

- The results of rolling a die

- The card number from a card randomly drawn from a deck

- Winning lottery numbers

- Birthdays aren’t perfectly uniform because they tend to cluster for a variety of reasons, but they are close to uniform

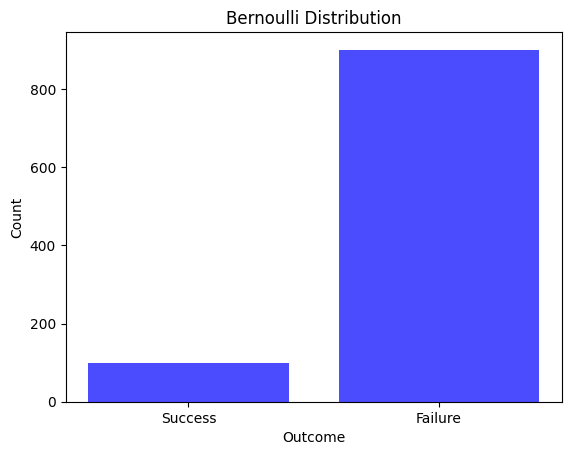

Bernoulli Distribution

The Bernoulli distribution is one of the simplest discrete probability distributions, serving as the basis for understanding more complex distributions like the binomial distribution. It represents the outcome of a single experiment which can result in just two outcomes: success or failure. The Bernoulli distribution is the discrete probability distribution of a random variable which takes the value 1 with probability p and the value 0 with probability q=1−p.

Plot

Consider an experiment with a single trial, like a medical test, where the probability of getting a positive (success) is 10%. To simulate this, we can do:

prob_success = 0.1

x = np.random.binomial(n=1, p=prob_success)

print(f"In this experiment, we got heads {x} times")

In this experiment, we got heads 0 times

This will output either 0 (no heads) or 1 (heads). To see the distribution of a large number of such experiments, we run multiple trials.

num_samples = 1000

data = np.random.binomial(n=1, p=prob_success, size=num_samples)

# Count occurrences of 0 and 1

successes = np.count_nonzero(data == 1)

failures = num_samples - successes

# Plotting

fig = plt.figure()

categories = ['Success', 'Failure']

counts = [successes, failures]

plt.bar(categories, counts, color='blue', alpha=0.7)

plt.xlabel('Outcome')

plt.ylabel('Count')

plt.title('Bernoulli Distribution')

plt.show()

Uses

The Bernoulli distribution is used in scenarios involving a single event with two possible outcomes. Examples include:

- Flipping a coin (heads or tails).

- Success or failure of a quality check.

- In essence, any situation where there is a single trial with a “yes” or “no” type outcome can be modeled using the Bernoulli distribution.

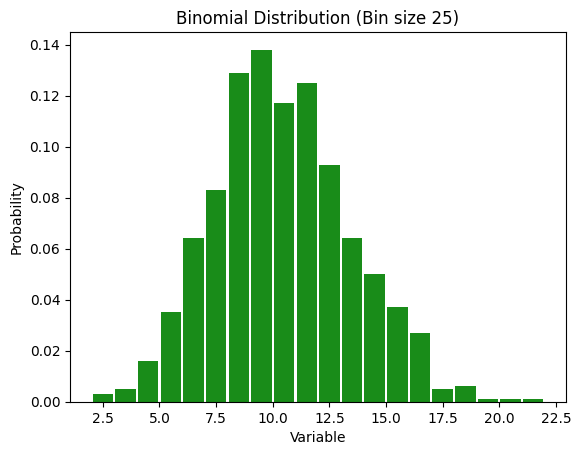

Binomial Distribution

A binomial distribution is a discrete probability distribution that models the number of successes in a fixed number of independent trials, each with the same probability of success. It is characterized by two parameters: n, the number of trials, and p, the probability of success in each trial. It can be considered an extension of the Bernoulli distribution we saw above to multiple trials. For large n and moderate values of p, its shape approaches a Gaussian (normal) distribution. However, with very large n and very small p, it converges to a Poisson distribution.

Plot

Let’s say with run something with 100 trials, each of which has a 10% chance of happening. To run that experiment, we can do:

num_trials = 100

prob_success = 0.1

x = np.random.binomial(n=num_trials, p=prob_success)

print(f"In this experiment, we got heads {x} times")

In this experiment, we got heads 7 times

But we can run this whole experiment over and over again and see what we get.

fig = plt.figure()

# Generate data

x = np.random.binomial(n=num_trials, p=prob_success, size=num_samples)

# you could also do this with scipy like so:

# x = binom.rvs(n=num_trials, p=prob_success, size=num_samples)

num_bins = 25

# Define bin edges explicitly to avoid gaps

bin_edges = np.arange(min(x), max(x) + 2)

# Plot the histogram

plt.hist(x, bins=bin_edges, density=True, color='g', alpha=0.9, rwidth=0.9)

plt.xlabel('Variable')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.title("Binomial Distribution (Bin size {})".format(num_bins))

plt.show()

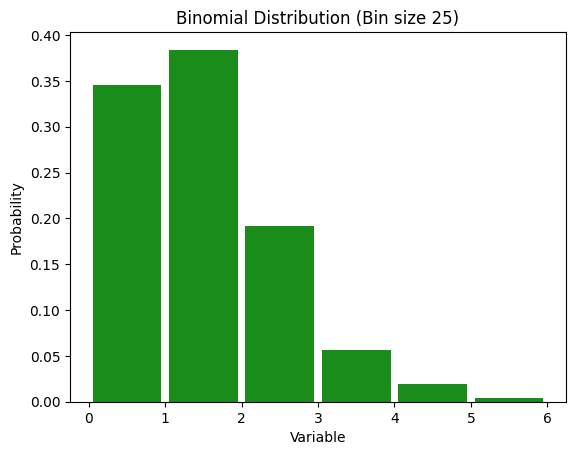

Small p version

num_trials = 1000

prob_success = 0.001

x = np.random.binomial(n=num_trials, p=prob_success)

print(f"In this experiment, we got heads {x} times")

In this experiment, we got heads 2 times

fig = plt.figure()

# Generate data

x = np.random.binomial(n=num_trials, p=prob_success, size=num_samples)

# you could also do this with scipy like so:

# x = binom.rvs(n=num_trials, p=prob_success, size=num_samples)

num_bins = 25

# Define bin edges explicitly to avoid gaps

bin_edges = np.arange(min(x), max(x) + 2)

# Plot the histogram

plt.hist(x, bins=bin_edges, density=True, color='g', alpha=0.9, rwidth=0.9)

plt.xlabel('Variable')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.title("Binomial Distribution (Bin size {})".format(num_bins))

plt.show()

Uses

- Flipping a coin

- Shooting free throws

- Lots of things that seem to be Gaussian but are discrete

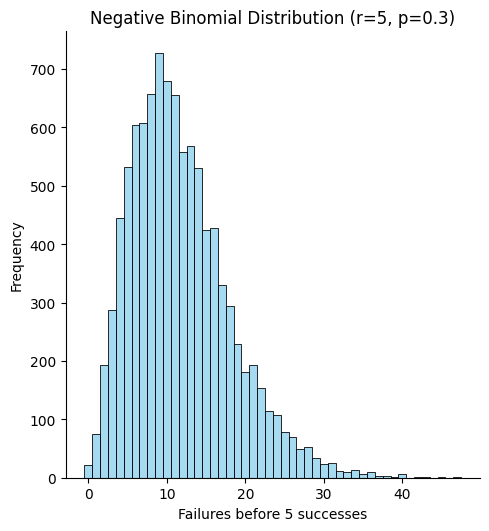

Negative Binomial Distribution

The negative binomial distribution models the number of failures that occur before a fixed number of successes is reached in a sequence of independent Bernoulli trials. Think of it as the sibling of the binomial: instead of asking “how many successes in n trials?” we ask “how many trials (or failures) until r successes occur?”

Parameterizations

- r – number of required successes (positive integer)

- p – probability of success on each trial (0 < p ≤ 1)

The probability mass function in the “failures‑before‑success” form is

\[P(X=k)=\binom{k+r-1}{k}\,(1-p)^{k}\,p^{\,r},\qquad k=0,1,2,\dots\]When (r=1) it reduces to the geometric distribution.

Plot

from scipy.stats import nbinom

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Parameters

r = 5 # number of successes we’re waiting for

p = 0.3 # probability of success

num_samples = 10000

# Generate samples (number of failures before the 5th success)

data_nb = nbinom.rvs(r, p, size=num_samples)

# Plot

sns.displot(data_nb, bins=np.arange(0, max(data_nb)+2)-0.5, color='skyblue')

plt.xlabel('Failures before {} successes'.format(r))

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.title('Negative Binomial Distribution (r={}, p={})'.format(r, p))

plt.show()

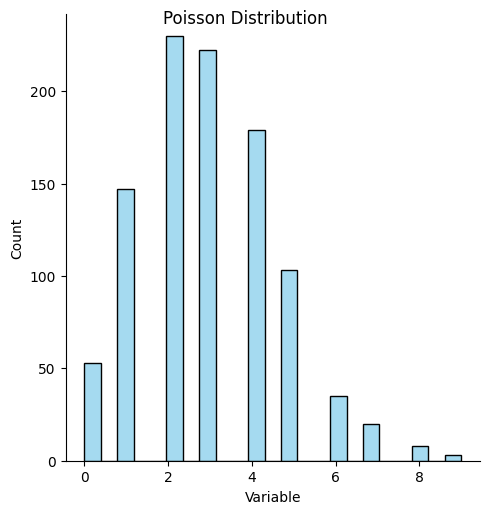

Poisson Distribution

Many real-life things follow a Poisson distribution. Poisson distributions are like binomial distributions in that they count discrete events. But it’s different in that there is no fixed number of experiments to run. Imagine a soccer game. So it’s discrete occurrences (yes/no for a goal being scored) along a continuous distribution (time).

At any moment, a goal could be scored. Thus it is continuous. There’s no specific number of “goal attempts” in a Poisson distribution.

If you wanted to find the number of shots on goal and see how many of them were goals, then it would become binomial. But if you look at it over time it’s Poisson. It’s like the limit of a binomial distribution where you have infinite attempts and each has an infinitesimal chance of being positive.

Note that Poisson and binomial distributions can’t be negative.

Equation

Mathematically, this looks like: \(P(x = k) = e^{-\lambda}\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}\)

Plot

data_poisson = poisson.rvs(mu=3, size=num_samples)

ax = sns.displot(data_poisson, color='skyblue')

ax.set(xlabel='Variable', ylabel='Count');

ax.fig.suptitle('Poisson Distribution')

Text(0.5, 0.98, 'Poisson Distribution')

Uses

- Decay events from radioactive sources

- Meteorites hitting the Earth

- Emails sent in a day

Example

Poisson distributions are very useful in predicting rare events. If once-in-a-lifetime floods occur once every hundred years, what is the chance that we have exactly five within a hundred-year period?

In this case \(\lambda = 1\) and \(k = 5\)

math.exp(-1)*(1**5/math.factorial(5))

0.0030656620097620196

If you wanted to calculate the probability of at least five once-in-a-lifetime floods, it would be:

from scipy.stats import poisson

lambda_val = 1

p_at_least_5 = poisson.sf(4, lambda_val) # sf = 1 - cdf

print(f"P(X ≥ 5) = {p_at_least_5:.6f}")

P(X ≥ 5) = 0.003660

Mixed Discrete and Continuous Distributions

There are many mixed distributions as well. I’ll go into detail on Tweedie distributions, but there are also zero‑inflated Poisson/negative‑binomial and hurdle models.

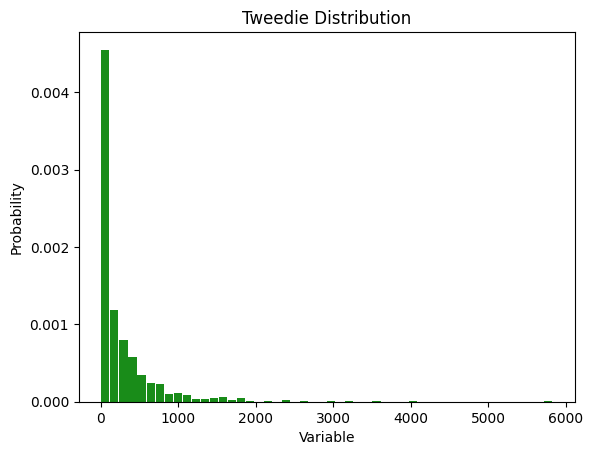

Tweedie Distribution

The Tweedie distribution is a family of probability distributions that encompasses a range of other well-known distributions. It is characterized by its ability to model data that exhibit a combination of discrete and continuous features, particularly useful for datasets with a significant number of zero values but also positive continuous outcomes. This makes the Tweedie distribution ideal for applications in fields such as insurance claim modeling, financial data analysis, and ecological studies, where the distribution of observed data cannot be adequately captured by simpler, more conventional distributions.

Plot

from tweedie import tweedie # download with `pip install tweedie`

num_params = 20

# Generate random exogenous variables, num_samples x (num_params - 1)

exog = np.random.rand(num_samples, num_params - 1)

# Add a column of ones to the exogenous variables, num_samples x num_params

exog = np.hstack((np.ones((num_samples, 1)), exog))

# Generate random coefficients for the exogenous variables, num_params x 1

beta = np.concatenate(([500], np.random.randint(-100, 100, num_params - 1))) / 100

# Compute the linear predictor, num_samples x 1

eta = np.dot(exog, beta)

# Compute the mean of the Tweedie distribution, num_samples x 1

mu = np.exp(eta)

# Generate random samples from the Tweedie distribution, num_samples x 1

x = tweedie(mu=mu, p=1.5, phi=20).rvs(num_samples)

num_bins = 50

n, bins, patches = plt.hist(x, num_bins, density=True, color='g', alpha=0.9, rwidth=0.9)

plt.xlabel('Variable')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.title("Tweedie Distribution")

plt.show()

Uses

Tweedie distributions are most common when values are a combination of zero values and some continuous values, such as the following:

- Insurance claims

- Number of each type of various species in an area

- Healthcare expenditures

Power Law Distribution

Power law distributions are pervasive in our world. These distributions describe phenomena where small occurrences are extremely common, while large occurrences are extremely rare. Unlike Gaussian distributions, power law distributions do not centralize around a mean value; instead, they are characterized by a long tail, where a few large values dominate.

Equation

The general form of a power law distribution is given by:

\[P(x) = Cx^{-\alpha}\]where

- P(x) is the probability of observing the event of size x

- C is a normalization constant ensuring the probabilities sum up to 1

- α is a positive constant that determines the distribution’s shape.

Pareto and Zipf’s Distributions

The Pareto and Zipf’s (pronounced “zif’s”) distributions are instances of power laws. Pareto distributions are more common with continuous data and Zipf’s distributions are more common with discrete data. They’re both very important so let’s look at them separately.

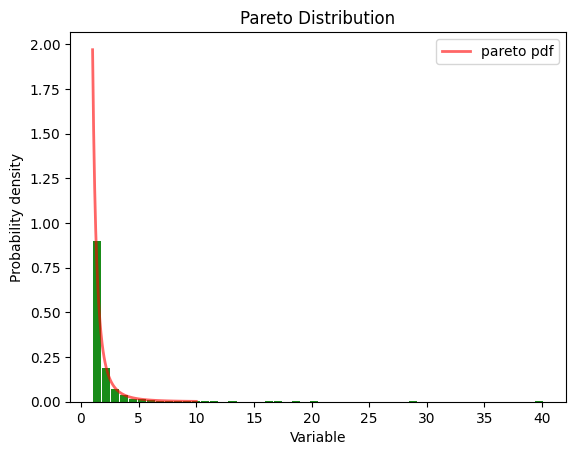

Pareto Distribution - Continuous

The Pareto distribution is a specific instance of a power law distribution. It was developed by Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto to model wealth and income. This distribution encapsulates the Pareto principle or the “80/20 rule,” which suggests that 80% of the wealth is owned by 20% of the population. The Pareto distribution is seen all the time, from social issues to scientific ones.

Plot

# Distribution parameters

a = 2.0 # shape parameter

b = 1.0 # scale parameter

# Generate random samples from the distribution

pareto_samples = pareto.rvs(a, scale=b, size=1000)

# Plot the histogram of the samples

plt.hist(pareto_samples, bins=50, density=True, color='g', alpha=0.9, rwidth=0.9)

# Plot the probability density function (PDF)

x = np.linspace(pareto.ppf(0.01, a, scale=b), pareto.ppf(0.99, a, scale=b), 100)

plt.plot(x, pareto.pdf(x, a, scale=b), 'r-', lw=2, alpha=0.6, label='pareto pdf')

plt.xlabel('Variable')

plt.ylabel('Probability density')

plt.title('Pareto Distribution')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

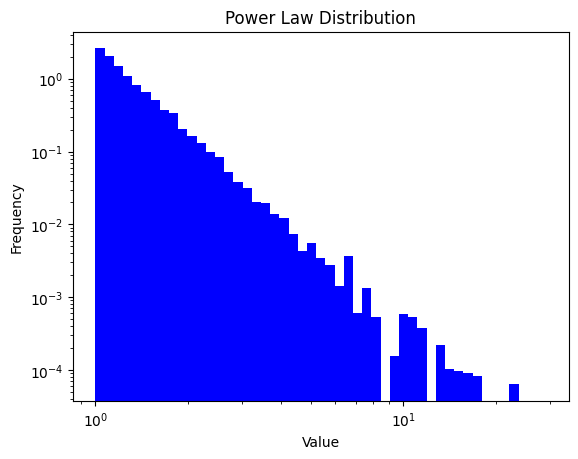

You can also generate them with numpy.

b = 3.0 # Shape parameter

samples = 10000

pareto_samples = (np.random.pareto(b, samples) + 1)

Note that the x values in the pareto distribution are continuous.

pareto_samples

array([1.67027215, 1.01475779, 2.95279024, ..., 1.58598305, 1.03600555,

1.55869634])

plt.hist(pareto_samples, bins=50, density=True, color='blue')

plt.xlabel('Value')

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.title('Pareto Distribution')

plt.show()

The linear plot is hard to see, so it’s common to plot it on a log scale.

plt.hist(pareto_samples, bins=np.logspace(np.log10(min(pareto_samples)), np.log10(max(pareto_samples)), 50), density=True, color='blue')

plt.gca().set_xscale("log")

plt.gca().set_yscale("log")

plt.xlabel('Value')

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.title('Power Law Distribution')

plt.show()

Uses

- 80-20 rule

- Income and Wealth Distribution

Recursive Nature

The 80-20 rule is recursive. That is, if 20% of the people do 80% of the work, you can zoom in on those 20% and find that 20% of those do 80% of that work. Note that this famous “80 / 20” split is a handy mnemonic, but it is only exact for a particular Pareto shape parameter (α ≈ 1.16). When the underlying distribution has that parameter, the pattern is roughly self‑similar: zooming into the top 20% again leaves about 20% of them doing 80% of what remains. In that special case you can approximate:

\[\text{share of people} \;\approx\; (0.20)^{x}, \qquad \text{share of work} \;\approx\; (0.80)^{x}\]for small integer (x).

For other shape parameters the exponents change—a heavier tail (α < 1.16) makes the concentration even more extreme, while a lighter tail (α > 1.16) less so—so treat the 80 / 20 recursion as an illustrative rule of thumb, not a mathematical law.

Here’s an example:

\((0.2)^x\) of the people do \((0.8)^x\) of the work for any \(x\).

For \(x=2\), this would be:

print(f"{(0.2)**2: .4} of the people do{(0.8)**2: .4} of the work.")

0.04 of the people do 0.64 of the work.

For \(x=3\), this would be:

print(f"{(0.2)**3: .4} of the people do{(0.8)**3: .4} of the work.")

0.008 of the people do 0.512 of the work.

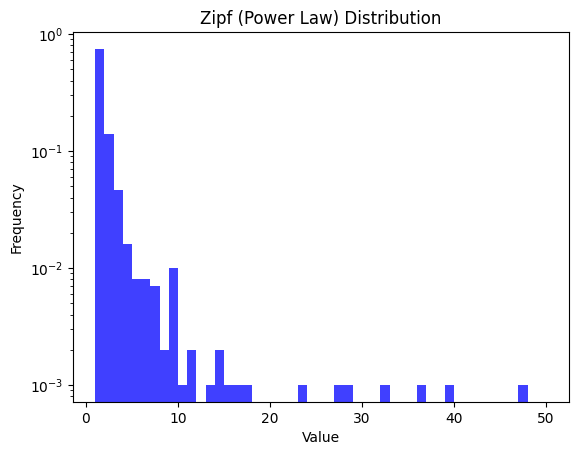

Zipf’s Distribution - Discrete

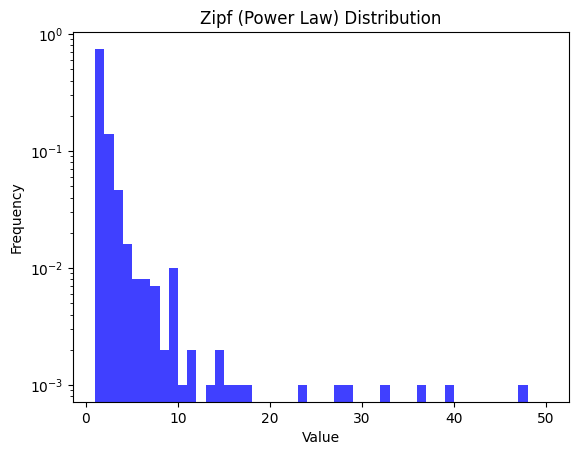

The Zipf distribution, or Zipf’s law, is another flavor of power law distributions, named after the American linguist George Zipf. It specifically describes the phenomenon where the frequency of an item is inversely proportional to its rank in a frequency table. Commonly observed in linguistics, where the most frequent word occurs twice as often as the second most frequent word, thrice as often as the third most frequent word, and so on (see this Vsauce video for more). Unlike the Pareto distribution, which primarily models the upper tail of distributions, Zipf’s law applies more broadly, capturing the essence of rank-size distributions.

Plot

alpha = 2.5

size = 1000 # Number of samples

zipf_samples = np.random.zipf(alpha, size)

# Plotting the histogram

plt.hist(zipf_samples, bins=np.linspace(1, 50, 50), density=True, alpha=0.75, color='blue')

plt.title('Zipf (Power Law) Distribution')

plt.xlabel('Value')

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.yscale('log')

plt.show()

Note that now the values are discrete.

zipf_samples[:10]

array([1, 1, 1, 5, 1, 3, 1, 1, 1, 3])

Uses

- Linguistics (word usage)

- Internet traffic (number of visitors to websites)

- File size in a computer

- Earthquakes