The story of rabbits in Australia, and the resulting eradication efforts, provides a cautionary tale about viruses and immunity. This post will explore the growth of that population and the government’s response to it.

Captive rabbits were first introduced into Australia in 1788 by the first European settlement - the penal colony at Botany Bay. The early settlers brought only five rabbits with them to Australia. The rabbits were kept for food and bred but never released into the wild. More rabbits subsequently arrived as settlements dotted the Australian landscape. They spread around Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen’s Land) but were mostly controlled on the mainland and didn’t spread into the wild. The settlers were able to keep the rabbit population in captivity and under control for over half a century until one thing happened - they got bored. They wanted to hunt rabbits as they did in England, and so, in 1859, they released 24 rabbits into the wild. From there, the population grew, like, well, rabbits.

To simulate the population, we’ll need an equation for population growth. The population will change by the growth factor, which is the difference in the birth and death rates, times the population size. Mathematically, this is written as:

\[\dfrac{\mathrm{d}P}{\mathrm{d}t} = P*(b-d)\]where

- \(\dfrac{\mathrm{d}P}{\mathrm{d}t}\) - change in population

- \(P\) - population

- \(b\) - birth rate

- \(d\) - death rate

The birth and death rates are usually combined into a single factor, the growth rate \(r\), where \(r=b-d\). We can plug this in and integrate the differential equation to give us the standard equation for exponential population growth:

\[P(t) = Pe^{rt}\]This equation works well enough in the beginning, but it misses a critical component - carrying capacity. Carrying capacity refers to the maximum population that the land can contain. There are limited amounts of food and shelter for the rabbits to survive, so at some point, they must reach capacity. We have to add a “carrying capacity factor” to the differential equation.

However, this doesn’t allow us enough precision. For example, rabbits don’t reach sexual maturity until 17 weeks - how do we factor that in? We’ll have to distinguish the sexually mature population from the rest.

\[\dfrac{\mathrm{d}P}{\mathrm{d}t} =P_m * (b-d) * (1 - P_{tot}/K)\]where

- \(\dfrac{\mathrm{d}P}{\mathrm{d}t}\) - change in population

- \(P_m\) - sexually mature population

- \(b\) - birth rate

- \(d\) - death rate

- \(P_{tot}\) - total population

- \(K\) - carrying capacity

Now we have to start plugging in the numbers. Rabbits have a gestation period of about four weeks, and each new litter of rabbits contains four baby bunnies. And there’s no relaxing, right after giving birth, they can start the process again. So if it takes two rabbits four weeks to make four baby rabbits, that’s a growth rate of about .5 rabbits per week for each rabbit. Rabbits in the wild live an average of roughly a year, so we’ll give them a death rate of .02.

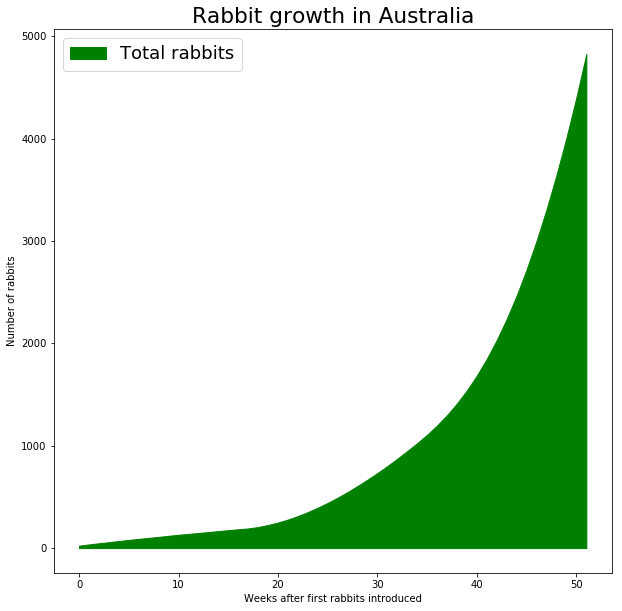

Let’s simulate the population growth for the first year.

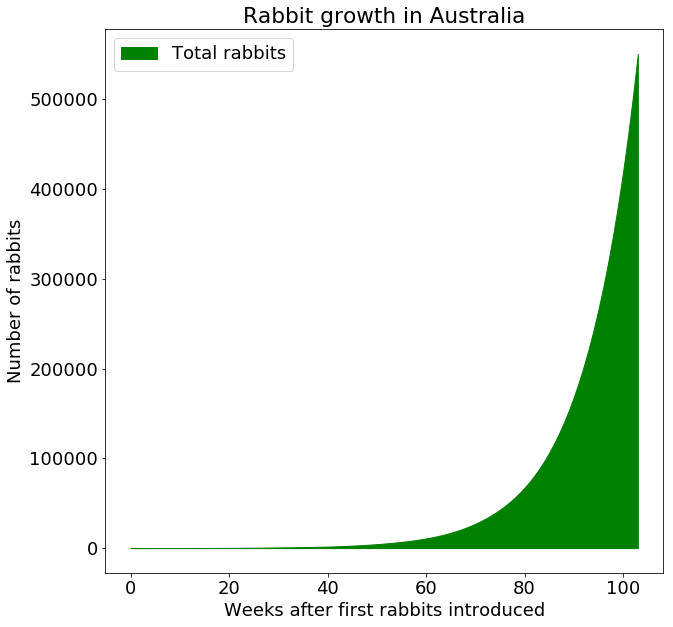

5000 rabbits. That’s a lot, but it’s manageable. But herein lies the problem with exponential growth. You may have a manageable number after a year, but after a second year you have:

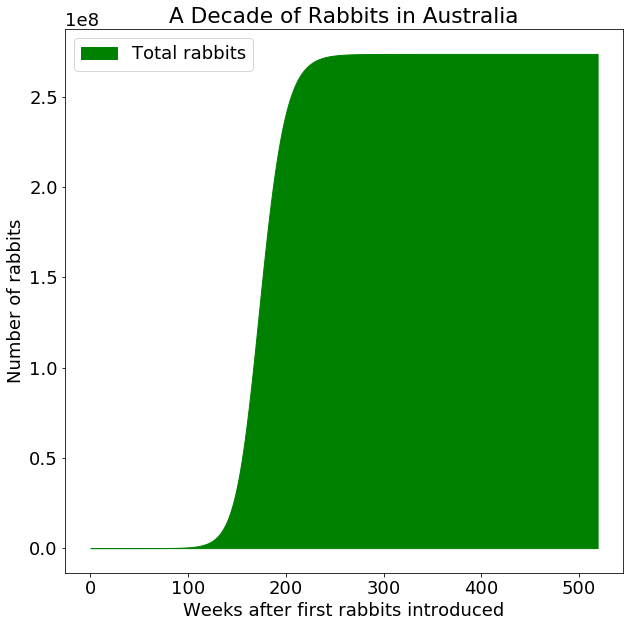

Half a million rabbits! It’s a classic example of unintended consequences. And given the expanse of the Australian landscape, the limit to the number of rabbits is enormous. Based on population estimates, the maximum population of rabbits in a vast country like Australia is in the hundreds of millions (remember, the human population is only 24 million). Based on the exponential growth of rabbits, they would be near this number in only four years. Due to the additional time it would take to spread proportionally throughout the country, it probably took a bit longer than that. Either way, it was the fastest spread ever recorded of any mammal anywhere in the world.

Obviously, hundreds of millions of additional animals competing for food, water, and shelter have a devastating impact on native wildlife. Their boundless appetites for vegetation decimate the native plant life. This, in turn, causes erosion, which leads to nutrient-poor soil. It wasn’t long before the Australian government determined that rabbits were causing significant economic damage. In 1887, the government of New South Wales started soliciting methods for removing them.

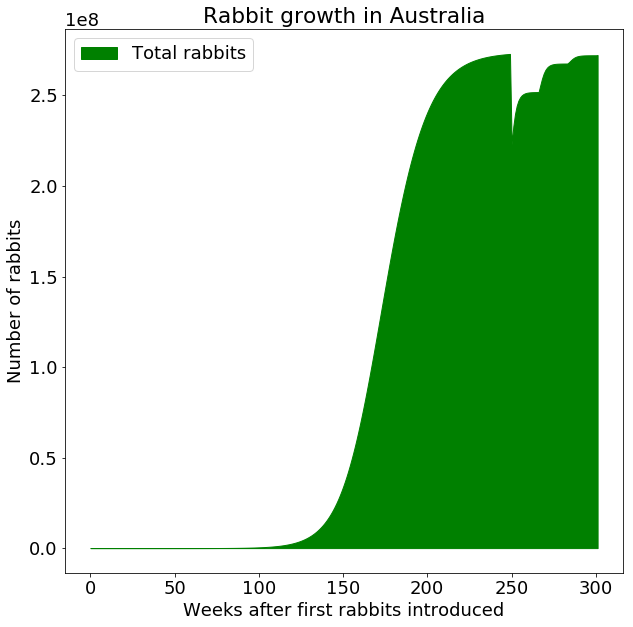

The most obvious method - hunt them, isn’t actually very effective. There were efforts to shoot, trap, and poison them. The efforts were expensive but ultimately had little impact on the robust rabbit population. To get an idea of the futility, imagine launching a tremendous rabbit hunting, trapping, and poisoning campaign that is so incredibly effective that it causes the death of 50 million rabbits in a single week. But the moment that expensive campaign is stopped, which would come eventually, the population regrows. Here’s a simulation of 50 million rabbits being killed in week 250. As you can see, within a year, the population has recovered.

But in the 1950s, after decades and decades of ineffective techniques, the Australian government tried something different - biological warfare. Viruses are incredibly effective at population control because after the target is infected, it finds new victims automatically, and the virus spreads by itself. The trouble is, how can you find a virus that’s safe to release in the wild but will not wreak havoc on the ecosystem?

The myxoma virus seemed like a perfect candidate. The virus spreads quickly, infecting several types of mammals, from rabbits to mice to humans. But only in the cells of rabbits can it replicate. And the replication causes the deadly disease myxomatosis, which can kill a rabbit within two weeks. But when it can’t replicate, as in the case with human cells, it’s harmless.

After some initial trials, the technique was approved and released into the rabbit population. The rabbit population was quickly cut in half, then in half again. The disease continued to spread and kill more and more rabbits. Based on the deadly efficacy of myxomatosis, the rabbit population should have been completely wiped out.

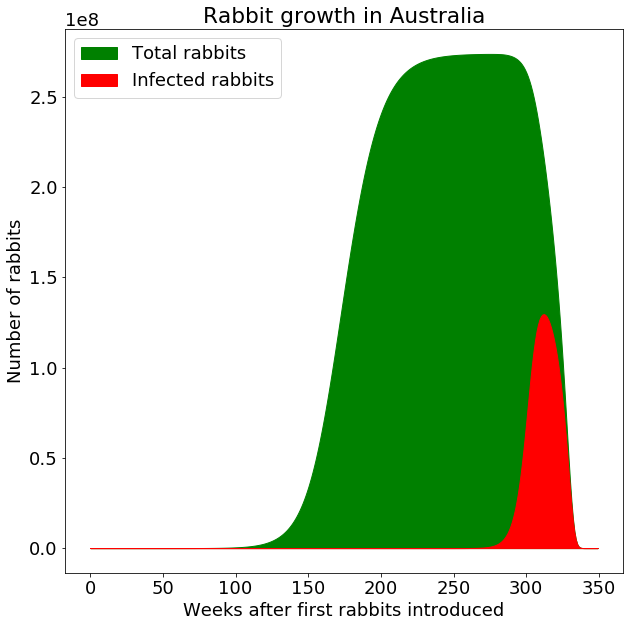

Assuming each rabbit spreads the disease to two others, this is the simulation of how it should have gone after releasing myxoma in week 250.

But that’s not what happened. The problem is, in any large population, there’s likely to be some members that, through chance genetic mutation, have natural resistance. This is true for nearly all diseases. Some people were naturally immune to the Black Death which killed half of all Europeans in the 14th century. Even HIV has a rival in people born with a mutation known as Delta32.

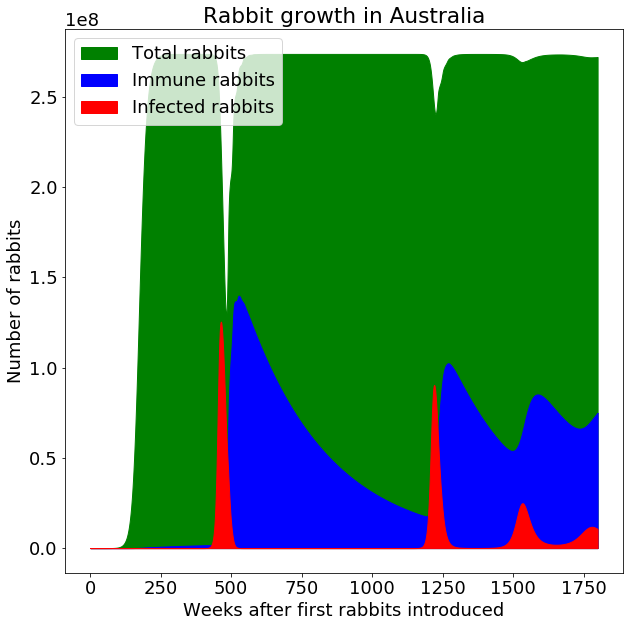

Myxoma was terribly effective on rabbits, but even if we assume efficacy against 99.99% of the population, there are still some with immunity. And once all the susceptible rabbits die, those with immunity breed and pass on their immunity to their progeny. Here’s a simulation with the same virality as before, but giving 0.01% of the population immunity, and assuming that immunity passes on to the next generation 99% of the time.

Although the virus has a significant impact initially, every time it starts to take hold, the immune rabbits, with no more competition from all those who died, spread across the land and themselves number over 100 million. And so, the myoma virus experiment ended, leaving Australia with a large population of mutant, disease-resistant rabbits.